Report card and progress report days are one of the most anticipated or dreaded events of a student’s year. For some, it is a day that will end with an email deleted or a paper thrown away to avoid a thunderstorm. For others, it’s the day where a row of shiny A’s will provide concrete proof of their endless work throughout the school year. But how much value do those A’s actually have with our changing school systems? The weight placed on those grades show insight into a wider societal problem: a growing dependency on academic validation within high school students.

Academic validation is a concept that has different meanings for teachers and students. For teachers, it constitutes more than grades, particularly with creating a feedback-based work environment. A 2011 study from UCLA defines academic validation from an educator’s perspective as “creating learning opportunities that empower students…and providing meaningful feedback.”

However, this takes on a different meaning for students. Academic validation is basing your self-perception on the grades that you earn, and having your sense of worth as a person be the result of how high-achieving you are. Oftentimes this comes from outside pressure–whether it’s from family, college applications or the school system as a whole–and has become a serious issue.

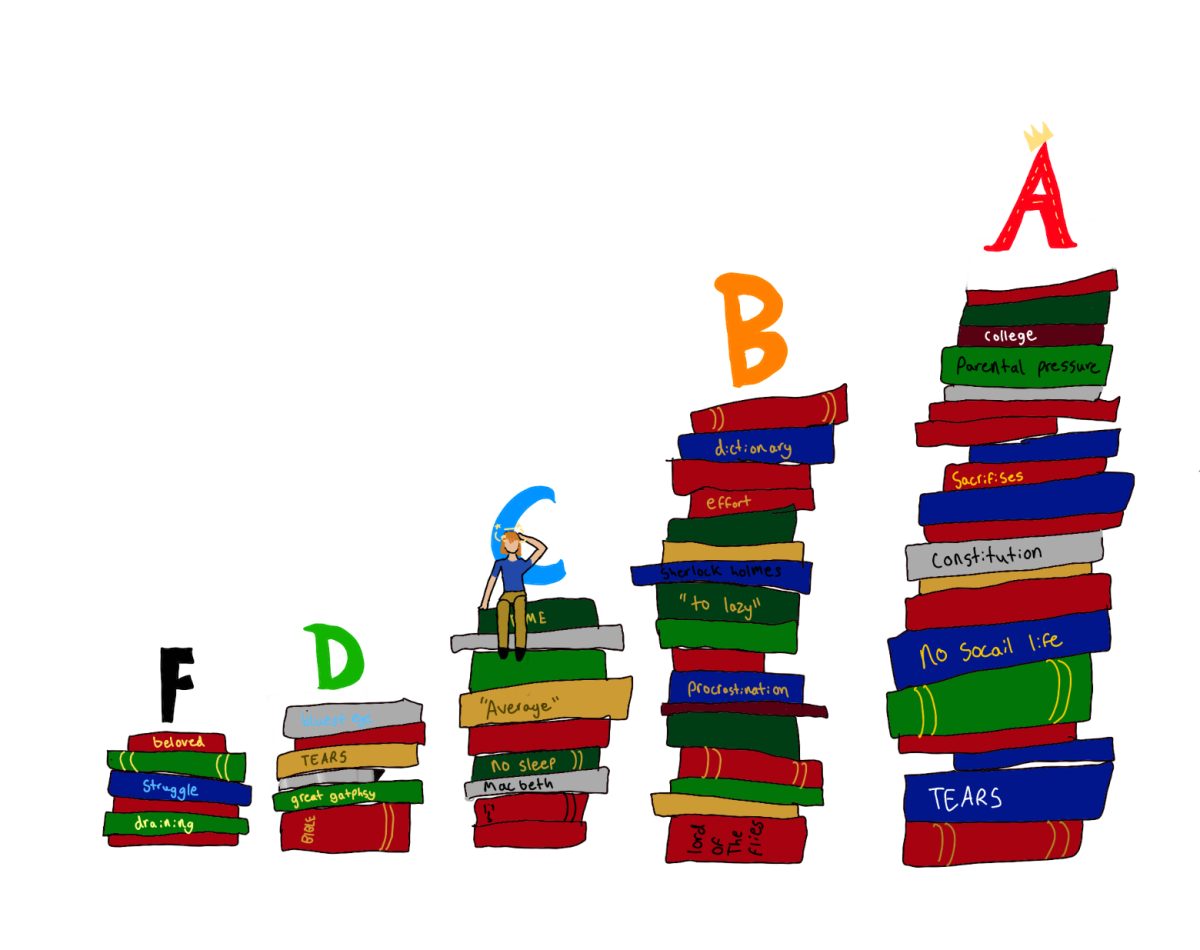

The widespread idea that you have to earn the right to be proud of yourself through academic achievement is not new, and it appears with nearly every student. As I’ve grown older, I’ve attempted to train myself out of the mentality that an A is the only grade that is acceptable. A B felt like I didn’t try hard enough or that I wasn’t good enough. And a C? I’d rather have a zombie apocalypse. My own self-esteem was a percentage on a page, crying and believing I should be punished if I received anything less than a 90%. The process of unlearning that idea has been a long, bumpy road, but a crucial one. It’s a dangerous mindset for your sense of self-worth to depend entirely on subjective grades.

It’s not only dangerous in terms of setting a shaky precedent for self-esteem, but searching for academic validation has serious mental health consequences. According to a 2019 report by the Pew Research Center, 70% of high school students surveyed believe anxiety and depression to be a major problem among their peers and 88% said they feel pressure about grades. Mental health issues are on the rise and being in a constant pressure cooker of achievement as an adolescent doesn’t help matters in the slightest.

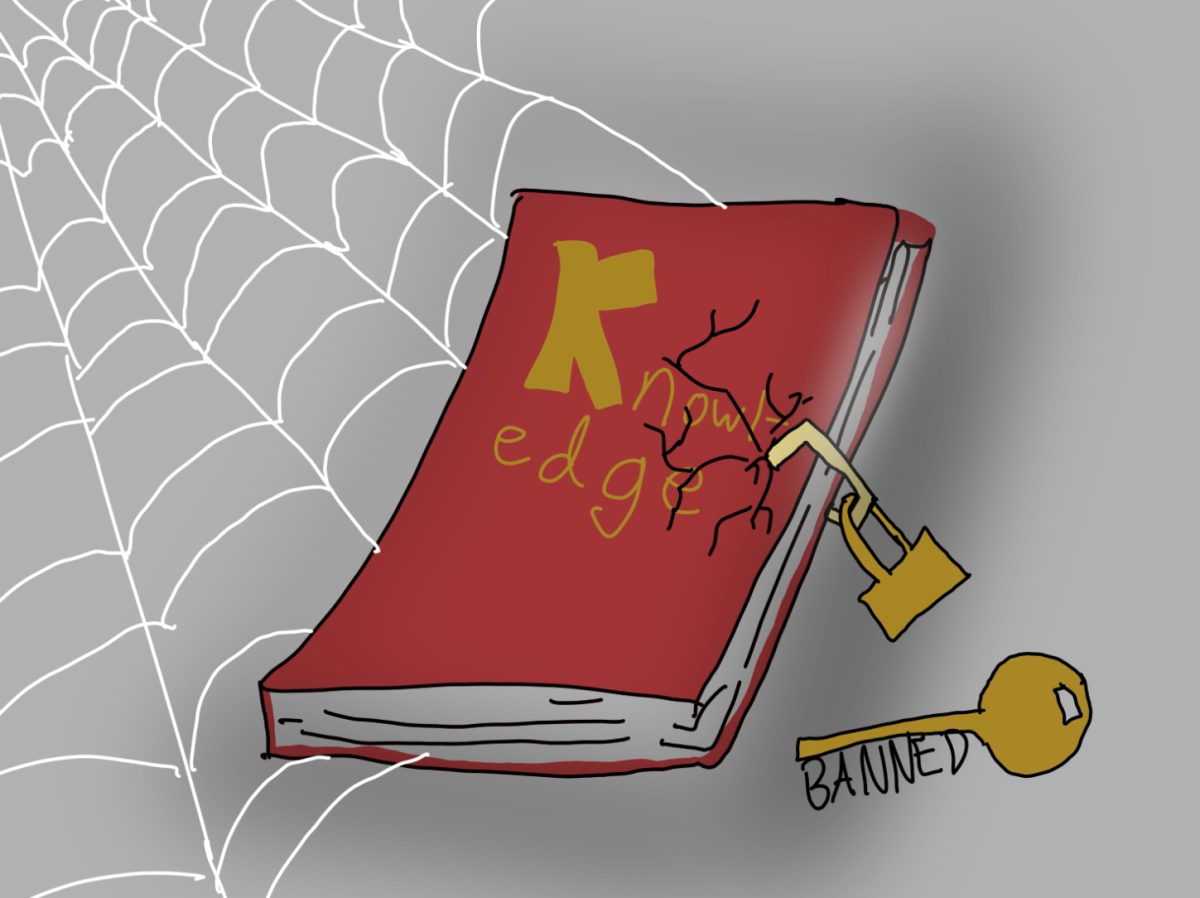

A large part of the issue is the idea of “busy work,” a term used for classwork that keeps a person busy but has little value in itself. This can be a reading assignment with needless annotations, a repetitive worksheet, or just generally an assignment that seems totally unrelated or pointless. San Domenico is not exempt from the plague of busy work pummeling high school students. Based on a poll from the Panther Press Instagram, more than half of San Domenico respondents agree that 50-75% of the work they receive in classes seems like busy work. However, a larger percentage of our grades are based on 3-4 assignments that make up a large percentage of the final grades, despite often having no meaning. You’re depending on those grades to maintain your high-achieving status, sometimes waiting weeks for teachers to grade assignments to make sure that you can still have that coveted A and any sense of self-worth. It creates a strange cycle of putting 100% effort into getting a good grade rather than 100% effort into understanding 100% of the material.

When discussing this issue, you can almost hear the Greek chorus of teachers and parents: “Grades are motivation!” “They show how hard a kid works!” “It’s the best way to measure a student’s progress!”

However, busy work and the paradox it creates with academic validation shows otherwise. Take two kinds of students: one who does the work regardless if it serves a purpose, and one who chooses to dedicate themselves to assignments they see value in. The student who does the work may have an A in a history class, but when it comes time for a test they couldn’t tell President Jackson from Johnson. The other student, however, may not be as interested in the assignment as they see no purpose in it, yet they have the understanding to write a 3-page essay on the topic with little difficulty. Not falling into the trap of busy work falsely sets the impression that the student doesn’t care about the class. The kids who are the most engaged in learning aren’t always the ones with the best grades, and the ones with the best grades are not the perfect students.

Being a high school student in the era of academic validation is like being stuck on a hamster wheel. It feels like you’re forever going through the motions of going to school and absorbing information just so you can feel like you earned that reward no matter the cost to your mental health. Students are not lazy or losing their priorities; we are exhausted from striving for success at every moment. Moving away from this mindset is not our responsibility or frankly, our job as students. Dismantling academic validation starts with a change in the system and it needs to happen soon.

Baharestan Rebekah W. • Mar 22, 2024 at 5:42 pm

Indeed! I’ve been saying this since the pandemic started- it is long overdue that k-12 Ed realizes the crisis on international level and we could have made this emotionally well caring change when schools went on hold in 2020. We had an opportunity to slow time to a humane pace yet the systems we all aspire within missed it’s moment – such a loss co all of society that we tried ever so hard to simply make it only just back up to the existing pace and Modus Operandi . The ever present materialism machine that churns at an already too chaotic pace .