Color drained from Weden when the winter came. The once vibrant pine forest slept, frigid, under thick white blankets. Sparse, naked canopies grasped desperately at the sky, teetering in the soughing December gusts. In the early mornings, the walls of the upland valley—towering, powdery eminences—cast their shadows on the streets of the town. The winding county creek—a tributary to the Pit River further east—flowed year round. In the winters, the edges would freeze over in glassy sheets, and when the sun eventually climbed above the peaks, the crystalline icicles that dangled from river rocks along the banks would form prisms, projecting brilliant colors onto the creek bed.

Weden housed a humble population of seventy two permanent residents, most of whom found their homes within a haphazard scattering of rustic, single–story cabins along the west end of the ravine. The downtown—a one pump gas station, a depressing, underlit corner store, the town hall–a relic of the forties–as well as the Aspen Diner, the only restaurant for miles in either direction—wasn’t much of a downtown at all. Weden City was an obnoxious overstatement of what was really a negligible intersection.

There were no road signs specifically pointing to Weden, not on the highway, or anywhere else. The sole indication of civilization in the valley was a rudely exuberant, green arrow at the turnoff that led to the town’s main drag.

Gas! Chow! Ammunition!

Peppered with bullet holes, it seemed comical to call it an advertisement when, in reality, it functioned as a repellent to any reasonable passersby. So, nobody had ever thought to take the sign down; the town’s curmudgeonly inhabitants weren’t exactly welcoming to out-of-towners.

And that was what I was there for, the blessing and the curse: solitude. Evelin had been opposed at first. She hated the cold, hated the mountain politics and the mentality that came with such isolation. More pressing though, she was expecting; fraternal twins, and she worried for them. We ultimately agreed, however, that the city would be worse for them. Following suit of other western cities, it had grown uncivil. With the council reallocating housing funds to drilling, homelessness had skyrocketed and crime rates with it. Evelin’s friends had all gotten out years before we eventually did, while mine, most of whom worked alongside me in the city police division, stayed for the raised salaries. But the city was starving. Cops started dying, being shot in the streets by members of disjointed gangs while on routine patrols. Stores began to close due to the rioting. And the rigs around the suburbs spewed rivers of smog into the air day and night; the reach of the suffocating, gray haze only grew wider. The city was dying and it was no place to raise children.

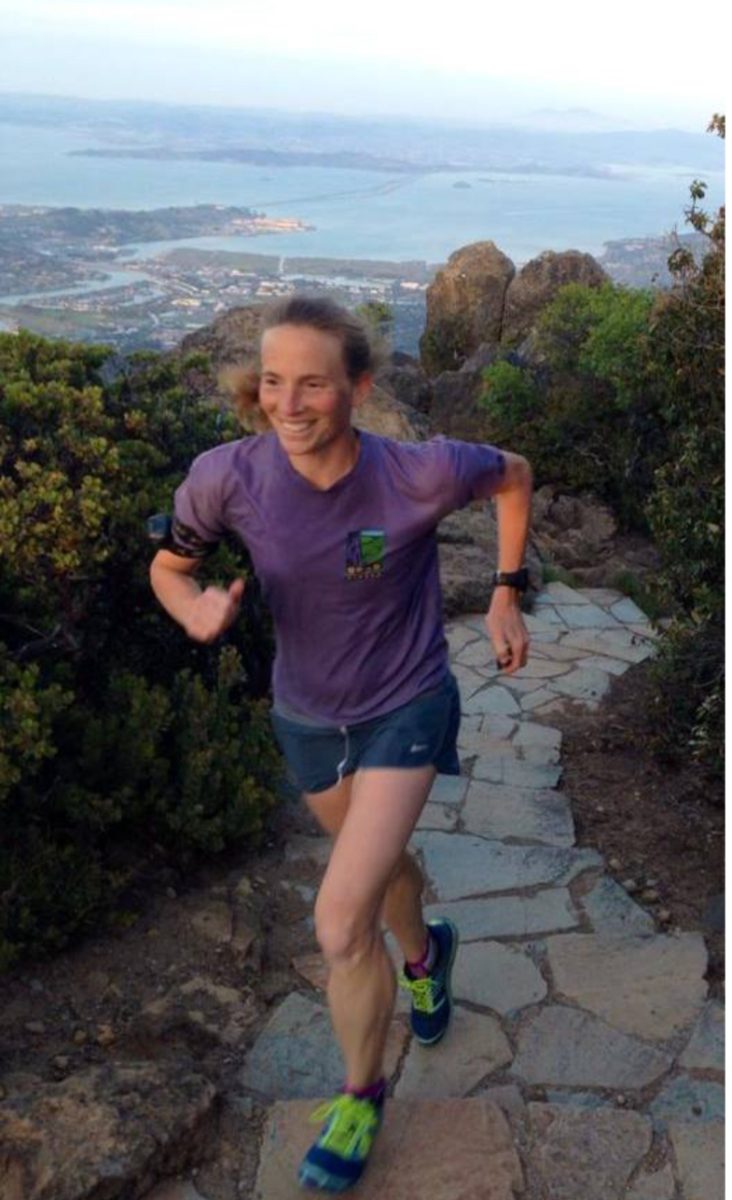

I had visited Weden once with my father when I was a boy. He would drive up each winter to watch the elk cross the horn of the great mountain. They marched by the hundreds, unrelenting, despite the biting cold. Unlike the other tourists, my father never skied, never hunted, and never stayed in the local lodges. He went out of his way to avoid people, sleeping out of his car and hiking out before sunrise to spend entire days on the horn. The one time he took me along, I was fourteen. We would hike the mountain in snow shoes each morning and break for lunch at the false peak with pastrami sandwiches and tea, listening to the elk wail. I loved Weden as my father had. The air was clear there.

Evelin took some convincing. She worried that I wouldn’t find work, that the kids wouldn’t make any friends, and that the townspeople would treat us like outcasts; all warranted concerns. Yet, I was crippled by idealism, not to mention my selfish craving for a change in lifestyle. She shared that desire, but my wife was more realistic than I was.

So we compromised. I would transfer from the city police, where I worked as chief criminal investigator, to the Weden City Police Department, where I would serve as the interim sheriff for eleven months. It would be a test run. We wouldn’t worry about looking for schools. We would rent a cheap cabin just off of the main road. We would go to the closest hospital, further north towards Mt. Shasta, if anything unexpected transpired. We would live, for a short while, away from it all.

…

The landline roared as Evelin left the table to take a call. It was Christmas and she had prepared her signature ham for dinner. The table was set with two wine glasses—she would only have a sip—her late mother’s set of china dishes, and one weeping candle.

“It’s for you, Des.”

I downed the remainder of my glass and mouthed, “Who is it?”

“Deputy Carol.”

I took the phone, kissing Evelin as we switched places. She smiled as she sat back down.

She was due any day then.

“This is Jules,” I prompted the voice on the other end.

Henry Carol, twenty five years old, wasn’t the worrying type, but he was shook that night.

The deputy was crying.

Evelin frowned as I dropped the handset back into its socket. My smile had faded and she

knew the look on my face, she had become all too familiar with it during our time in the city. “Des–”

“Evelin,” I shook my head, “I don’t—I’m sorry.”

“Tonight, really?” her face grew red. I just stared, what could I say? After a beat of silence, she thrust her arms across her place at the table, flinging her setting to the floor. A plate shattered and the bottle of wine that we had been saving spilled out onto the checkered rug. She was furious as she kicked her chair back against the stone wall of the dining room, vehement eyes locked with mine. I advanced, hoping to console her, to help her understand that I didn’t have a choice. It was true, but I knew it wouldn’t help. This was the job and the damage had been done twenty years ago when I joined the academy. Her reaction was a culmination of her frustrations with me since we had moved, four months earlier.

She stormed out of the room and slammed our bedroom door behind her. I followed timidly and leaned against the frame, “Evelin, I’m sorry, I am. But they need me tonight. This will be the only time, I promise.”

I waited. Nothing.

“I may be out late, don’t wait up for me,” I sighed.

Nothing again.

“I love you,” I stood beside the door for a moment, rocking side to side. The silence was

deafening.

“I love you too.”

Relieved, I hurried down the hall and grabbed my coat from the rack on the wall. Beside it hung a picture of Evelin and I riding horses at her uncle, Charles’ ranch in Auburn. Gazing at the scene, I felt ashamed. We had left for Weden to escape the commitments of city life, yet there I was, leaving, as I did so often back in the city. I unlatched the thick oak door, swung it ajar, and embraced the cold as I sprinted to my Ranger.

…

Resting at the base of the region’s tallest mountain, Weden had been erected hurriedly in the forties upon the discovery of a substantial haematite deposit within the mountain’s winding caverns, which would serve in the production of bullet casings during the war. Fifteen families, the sole residents at the time, woke each morning in ramshackle cabins to see their fathers and husbands off to the caves. Nearing the end of the war, after months of work, the miners supposedly pierced the stone wall of the Weden Spring, flooding the deeper caverns. The townsfolk—wives, sons, daughters—had heard their frantic screams. The ravenous flow of mineral–infused water had allegedly eaten away at the unstable, wooden support beams. One after another, they snapped under the colossal weight of the stone ceiling, echoing throughout the cave. The workers’ screams grew quieter with each snap. Eventually, only the screams of the elk above filled the air.

The mountain adopted a bad omen of sorts that day and the town was abandoned by its fifty some inhabitants shortly after, left derelict for many years. Sometime in the sixties, volunteers, including one Thomas Jules, the old man himself, had resurrected it. The cave, however, remained closed indefinitely.

…

From what I had picked out of Deputy Carol’s stutterings, someone had been found at the mouth of the Weden caverns by hunters. A boy.

There were blizzard conditions that night, and the roads were slick with a fresh layer of snow. I fumbled with a pack of cigarettes as I swung around the corner of the station, sweating. The truck screeched to a stop and I launched out, lighting a smoke as I jogged inside. I ran past the front desk, where officer Kane, an older, rough looking fellow had dozed off, speckly drops of milkshake dribbling down his red beard. He groaned as I burst through the door of my office. I snatched my rig from my desk and shot back down the hall. Again, Kane groaned.

Beside the car, I holstered my state issued Glock 17 and fastened my utility belt to my jeans. My hands were stiff from the cold as I drove in a trance, to the north edge of town, where the caverns opened up to the ravine. Carol was there, corralling a mass of onlookers. He sprinted to the truck, slipping on his way.

“Jules,” he exclaimed shakily, “I tried shielding him from the snow, but this wind, and the people, and I—”

“Relax, you did the right thing. You called forensics?”

“Already on their way.”

“Good. We’re losing time in this storm. Get them out of here,” I motioned to find the perimeter.

The scene had attracted what seemed to be the entire town; a shifting crowd of crumpled faces, erupting with inquiries from behind the wavering caution tape. Crime, I mean, real crime was generally infrequent in Weden. There was, of course, your typical neighborly mountain man thievery of lumber, though the Department preferred to remain uninvolved in such petty matters. There were, after all, only ten officers on the force, including myself. Things like this simply didn’t happen in Weden. Carol obliged, and began clearing the mob.

I shifted to see a limp figure laying bundled in a dull blue tarp at the gaping mouth of the cave. Kneeling, I winced as I pulled back the layers to observe the remains. The poor boy must have only been seven, maybe eight. Entirely disfigured. It looked like an animal had done it, but the wounds were calculated; perfectly lethal cuts about the neck. He was dead before he had been mangled. A colony of snow fleas had flocked to where the boy’s head rested, bloodied, against the icy earth.

I leaned back against a heap of powder as the freezing drafts flicked the tarp back and forth. My eyes stung. I wasn’t crying, it was only the cold. But I felt heavy. Somehow, it all reminded me of the city; the wind, the sour smell of decay, the sinking in my chest. I exhaled, fighting every urge in my body to tamper with the scene; there was nothing I could do, it was no longer my place to poke and prod. I would have to wait for forensics.

The cave looked endless, only faintly illuminated by the strobing blue and red from Carol’s Ranger. As I sat there, a packed clump of snow tumbled from above the opening, crumbling at my feet. I gazed above as a shrill cry rose from atop the mountain. It echoed across the valley and down into the caverns in an eerie dissonance. The elk had returned to the horn.