With over 10,000 properties reduced to rubble, 28 lives lost and more than 150,000 residents displaced as of now (equivalent to San Rafeal, San Anselmo and Fairfax residents times two), the Los Angeles fires have carved a devastating path through Southern California.

The Los Angeles fires are not the first time California has faced devastation due to intense winds. The state’s dry climate and flammable vegetation, combined with rapid winds make it a hot spot for wildfires. Historic wildfires such as the Tunnel Fire in Oakland Hills in 1991, Cedar Fire in San Diego County in 2003 and Tubbs Fire in Napa and Sonoma in 2017 resulted in immense casualties and have left deep scars on CA; however, the recent fires in Los Angeles, including the Palisades and Eaton Fires are rapidly rising among the most destructive and already are the most expensive in the state’s history.

Despite the overwhelming damage and intensity of the Los Angeles wildfires, firefighters across the country have had remarkable success in containing the Eaton Fire by 95% and fully extinguishing the Palisades Fire. Their unwavering dedication to saving homes, clearing debris and rubble and dousing fire hot spots ultimately brought the fires under control. Beyond containment, there are still thousands of firefighters aiding with the rehabilitation process and recovery, as well as search-and-rescue efforts. Currently, there are 4,000 firefighters battling the Hughes Fire, according to the New York Post.

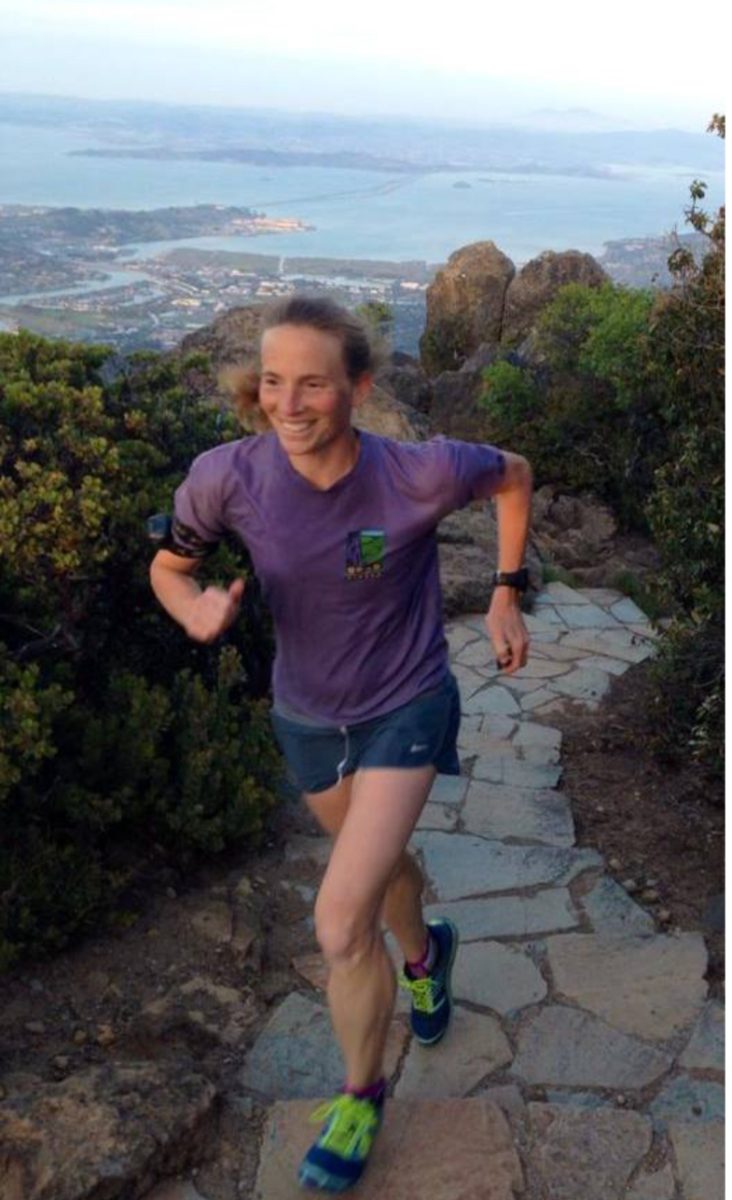

Several firefighters from our local Tiburon Fire Department, including Steve Ardigo, Mark Fitzgarald and Digory McGuire, were deployed to the Los Angeles fires, each with distinct roles, titles and assignments.

Ardigo, a Battalion Chief, spent 10 days at the Eaton Fire, which burned in the Altadena and Pasadena areas of Los Angeles. As a Task Force Leader, Ardigo oversaw five engines, and a total of 20 men and women from Marin County that were dispatched to combat the blaze.

Ardigo said the destruction and devastation from the Eaton Fire was “off the charts.”

“I’ve been a firefighter for 27 years, and I have never seen anything like that,” Ardigo said. “There were 1000s of homes burned to the ground. It was city block after city block of burned out homes. It looked like a nuclear bomb had gone off.”

During his 10 days at the Eaton Fire, Ardigo took on a variety of assignments while leading his task force, working grueling 24-hour shifts. He and his men were doing everything from putting out structure fires, providing structure protection and building in defensible space around homes to prevent them from burning if the fire escaped containment.

During his first two shifts, Ardigo’s task force was assigned to the burned out area of the fire, where most of the homes were lost. They responded to calls for service, called in by police or other residents patrolling the area who gave them information on burning structures or other tragedies. The firefighters searched for hot spots and flare ups inside the fire perimeter.

Unlike a forest wildfire, suburban conflagration fires have roads already paved, allowing firefighters access to the center of the fire where the hot spots flare. With a focus on saving the remaining structures, firefighters raced to extinguish any flames within the interior of the incident. They drive into the heart of the flames in order to save houses, putting their lives at risk.

“[The danger] is probably always in the back of your head, but you just have faith that you can rely on your knowledge, skills, experience and training to get you through whatever needs to be done,” Ardigo said.

Additionally, Ardigo is motivated by the positive impact he has on communities. Whether he is saving homes, lives, or cleaning up rubble, knowing he is helping people urges him to keep persevering.

While Ardigo was working he received a call from his cousin, inquiring about her friend’s house that happened to be in the burned out area. She wanted him to check on it. Ardigo was nervous: the probability it was still standing was low, but when he finally arrived, the house was still there. He called his cousin and shared the unbelievable news about her friend’s house: “She started [to bawl] her eyes out, crying tears of joy,” Ardigo said.

“It was a little ray of sunshine in a really dark time, but it felt really good to be able to let someone know their house was still standing,” Ardigo said.

Susan Ardigo, Steve Ardgio’s wife, details her mixed emotions after being told her husband was deployed to the Eaton fire.

“When you get the news that they are going, you’re nervous, but also incredibly proud,” Susan Ardigo said. “He’s doing something really important.”

In addition to Ardigo, Fitzgarald, a Captain/PM at Tiburon Fire Department with 20 years experience, was deployed to the Eaton Fire in an Urban Search and Rescue Team (USAR).

Because the USAR team is typically reserved for earthquakes and other natural disasters, it was Fitzgerald’s first time walking through entirely burned homes and doing the tedious, yet vital work of a USAR team member. Their main objectives were to, first, repopulate the area and lift the evacuation. And second, to account for everyone missing and give people closure and answers.

Before the search, a paleontologist debriefed the team of 30 people on what severely burnt remains look like. Afterwards, the firefighters went about the searches in a couple steps. First, they would hastily walk through the neighborhood the police assigned to them that day, taking note of the houses burned and get an idea of the area. Next, they conduct a primary search, consisting of walking around the house perimeter and looking in the bathroom and bedroom, areas most likely to contain potential remains. They spent extra time on houses assumed to be occupied, deduced from factors like having two cars in the driveway. After their first home search, firefighters would come back and do a second, more in depth search, pulling off walls and moving debris.

“Sometimes you don’t even feel like you could say for sure that there was no one there because of the amount of burnt debris,” Fitzgerald said. “What if [victims are] buried? Or what if [victims are] crushed or underneath something?”

If the team does feel as though they have discovered remains, they report it on Star Cop, a new tracking and uploading app the USAR team used.

“It was just a different version of LA than the norm. We go into these areas that are evacuated, and it just didn’t look like there was ever a neighborhood there [at all],” Fitzgerald said. “Sometimes every few blocks there was one standing home.”

Fitzgerald comments on how the job made him further realize the impermanence of everything and reflected on how surreal it is that “these neighborhoods that you and I live in can just kind of disappear.”

Fitzgerald understands how significant people’s homes are to them, some people living 50 plus years in one house with a lifetime of memories. The vital work of saving people’s homes and lives is one of the main reasons Fitzgerald became a firefighter in the first place.

“[Firefighters] want to go help all the time, and so we get very excited at the opportunity to combat something destructive, protect people’s lives and their property,” Fitzgerald said. “That’s why we do the job.”

Fitzgerald describes firefighting as being a good community member or neighbor, but with equipment and a great deal of professional training.

“I love that I have a job that I get to have the opportunity to help people when they need help,” Fitzgerald said. “That’s why it doesn’t feel entirely like a job all the time.”

McGuire, a lieutenant, was deployed to the Palisades fire as an Engine Boss and in charge of four people. McGuire was at the fire for days, his dedication and hard work were evident when he refused to come home after the mandatory 14 days were up. He has recently been reassigned to fight another fire in San Diego.

McGuire’s base camp was established at Zuma Beach in Malibu, and his strike team was assigned to “Division Uniform” in the Monte Nido neighborhood of Malibu Canyon. Their task was to head to Saddle Peak for structure defense, extinguish hot spots around savable homes and tactically patrol the area. They worked 24 hour shifts, monitoring changing weather conditions, particularly the predicted Santa Ana winds of 60+ mph especially in higher elevations. Their focus was on mitigating hot spots before the winds intensified in the afternoon.

When a structure is in imminent danger, the team evaluates its defensible space, fire activity and alignment with weather factors like wind and topography. If deemed defensible, they deploy hose lines to extinguish hot spots, wet down the area around the house (including the roof), and monitor for embers entering the home. Vegetation around the house, especially larger fuels or radiant heat sources, is also addressed, even if the structure has defensible space with minor threats. If a structure begins to ignite, they shift to active cooling to prevent further damage.

McGuire comments on the dangers and responsibilities of being an engine leader, and how vital the three other people on his engine safety are to him.

“Their lives matter to me, essentially more than mine, because I want to make sure that they can come home safe to their families,” McGuire said.

McGuire understands that firefighting can be a dangerous profession and explains how it is about toeing the line between putting yourself out there for the greater good and being good to yourself at the same time.

“It absolutely takes a toll emotionally, because there are sometimes where you feel like you’ve given it your all, but you still end up losing,” McGuire said. “[sometimes] there’s just things that you can’t do.”

Between Jan. 7, when the Palisades Fire started, and Jan. 27, a confirmed 6,837 homes were decimated, 23,448 acres were burned and eight people died, according to NBC News.

Despite the devastating statistics, the Palisades Fire could have been significantly worse if there were not willing firefighters to put themselves in harm’s way, leave their families for a couple weeks and spend emotional and physical energy dedicated to selflessly helping others.

Luckily, the Palisades Fire is 95 percent contained and the evacuee orders have been lifted. McGuire is now in the clean-up process, mitigating any hazards, like power poles across the road, power lines on people’s homes and anything dangerous once the public comes back to their homes.

“We’re trying to make the repopulation as welcoming as we can, regardless of the devastation,” McGuire said.

At this stage, it is all about bringing the community back together, welcoming people home and being respectful. The firefighters do their best to show the communities that they are working hard and doing everything that they can to get people back to their homes, whether they’re still there or not.

McGuire has had many interactions with community members and evacuees, many of whom are extremely appreciative and have immense gratitude for them. One woman he encountered started bawling the second she saw him. McGuire held her in his arms and assured her that the firefighters were doing all they could and were there to support her with whatever she needed.

“I think the biggest message is, at any desperate time of need, the fire service always has people’s backs,” McGuire said. “We really do care. We want to do the best that we can with their safety and their property in mind. And we’re doing everything that we can with what we have to make the best outcome.”