The UC staff are striking. That’s a good thing.

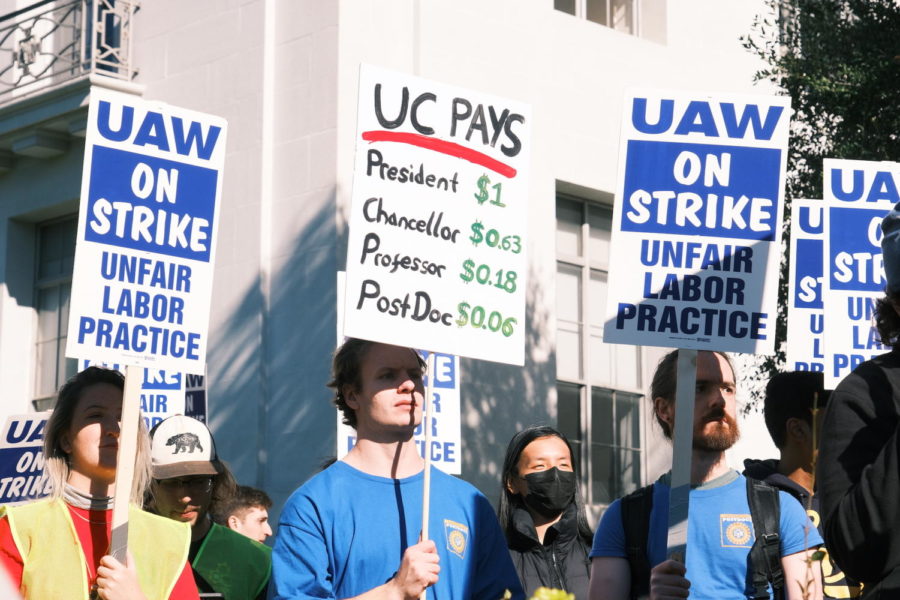

Workers protest at UC Berkeley, Nov. 2022. This comes amidst negotiations for higher pay and other benefits by UC UAW union members. (AP Photo/Ian Castro)

December 15, 2022

CALIFORNIA — An academic worker at UC San Diego finishes their 45 min commute home after payday, knowing over half of what they just earned will be devoured by their rent. They realize they have no choice but to get a second job.

Nov. 14, 2022 — The University of California system cancels many classes as 48,000 of its workers participate in one of the nation’s largest labor strikes in recent history, according to the New York Times. This comes after over a year of failed union negotiations with the International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW), who represent postdoctoral workers, graduate student researchers and instructors, academic researchers, and more.

While the need to strike is always regrettable, UC workers deserve to have demands heard.

Let’s take a look at what brought us to a strike of almost 50,000 strong in the first place. One of the most prominent issues for members of the UAW is that their pay doesn’t match their rent costs. An internal survey by the UAW concluded that 92 percent of UC Graduate Workers and 61 percent of Postdoctoral Scholars pay over 30 percent of their pre-tax income on rent alone. This qualifies them as “rent-burdened” by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development, which has been linked to a host of negative life impacts.

As an organization with over $40 billion in revenue, paying a wage high enough to afford housing seems within grasp for the university’s system. It is also critical to the healthy functioning of the university as a whole.

Fairucnow, a website organized by the struggling UAW members, claims “Our proposals at the bargaining table are what’s needed so that we can focus on our work – as opposed to how we’re going to make ends meet.”

If the University of California wants a productive workforce, step one would be ensuring that their employees aren’t struggling to dodge homelessness and starvation. That involves paying them enough to afford both housing and groceries.

The striking workers have other steps they want the UC system to take as well: increasing the length of job appointments to increase job security, expanded childcare and family leave benefits, and the abolition of non-resident supplemental tuition fees for student employees.

These, too, are reasonable requests.

Short job appointments allow for supervisors to manipulate employees into letting abusive behavior go unreported with the knowledge that reporting incidents could mean not getting re-appointed next cycle. They also cause a significant amount of time to be wasted for both employees and administrators who are forced to spend hours bogged down in paperwork filing for and approving short term appointment extensions.

Childcare and family leave are similarly important. If you’re a new parent without childcare and family leave, your options are typically limited to ignoring your child, or somehow finding enough money to quit your job and take care of your kid. If UC wants to retain non-distressed workers, these benefits are a must.

University of California, as a state-funded institution, aims to confer the benefit of attending university at a lower cost to in-state students. According to the University of California website, “Waiving tuition for out-of-state (including international) student employees puts California resident students at a financial disadvantage, as doing so would effectively give non-resident students a larger compensation package than resident student employees for doing the same work.”

The University of California is factually correct about that. However, giving a path to education for non-resident students who contribute to and improve the school is a good thing, even if it slightly diminishes the financial advantage California residents have. By waiving out-of-state tuition fees for non-resident employees, the University of California would make the overall quality of education increase for California resident students. By increasing the pool of qualified workers—people doing research, teaching, and assisting at the school—UC makes a better environment for all of its students

To UC’s credit, they’re actually highly competitive when it comes to worker compensation and benefits in the realm of U.S. universities. Their pay scale is among the highest of the nation’s leading public universities, and they already provide some (if not nearly enough) housing for student employees at below market rates. The problems are mostly symptomatic of a larger housing crisis in California and a national lack of strong protections for workers.

Nevertheless, competitive as UC might be to other academic institutions, it still stands that their workers are having enormous issues working for and living near them, and that UC has the power to fix them. The University, an institution funded by and in service to the public, is capable of decoupling their housing prices from the market completely. If their employee wages and benefits are competitive, but still lacking for basic necessities, they have the power to deviate from the national standard. The UC system needs to do what is best by the people that work for them, regardless of whether other universities are doing the right thing.

They seem to have realized that, at least partially.

As of Nov. 29, UC has come to a tentative deal with the UAW regarding postdoctoral scholars and academic researchers that meet many of the union’s demands. If ratified, those workers will get 8 weeks paid family leave and a significant pay raise, among other benefits. But deals for the other workers are still withering on the negotiation table.

It is important to recognize that it’s uncertain any of these improvements would have happened if the Union didn’t strike in the first place. When initial negotiations fail, striking is the only option workers have.

As prospective UC students and parents, it can be tempting to fear how a strike might impact you or your child’s education, but I urge you to stand in solidarity nonetheless. These workers are only trying to make a living, just like everyone else. In the long run, happy workers equals a better education, even if it has negative short-term impacts.